On Feb. 20, the Art Gallery of Peterborough (AGP) opened what may be their strongest exhibition in recent years.

Fynn Leitch (AGP Curator) expressed her excitement about the exhibition. She was thrilled “to see all the work in the space, on the wall, and all the people here enjoying them.”

Working on this project was “really gratifying,” Leitch continued, and it is a“tremendous achievement for the AGP.”

One major exhibition and two smaller ones are on display until May 22.

The major exhibition is a collection of paintings and drawings by Arthur Shilling (1941-1986). Curated by William Kingfisher, The Final Works consists of works from private and public collections.

The greatest achievement is Kingfisher’s efforts in assembling together these disparate pieces. During his speech at the opening reception, Kingfisher stated that this exhibition is indeed “what Arthur would have wanted.” Some of the works have not been exhibited previously.

Shilling, born on the Rama Reserve near Orillia, seemed to work primarily in portraits during his final years.

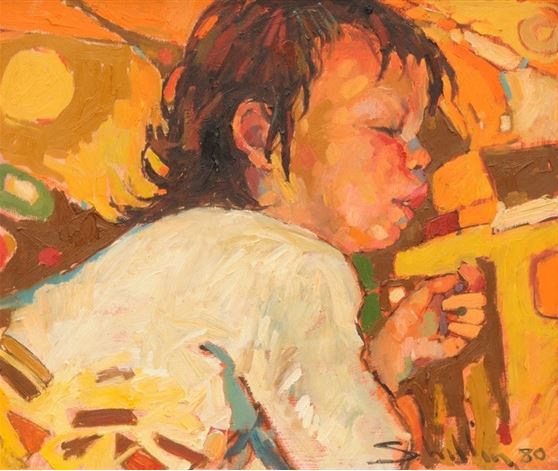

What we notice on Kingfisher’s curated walls, however, is that even during these “final years” Shilling was an artist still honing and developing his style. Some paintings are wonderfully impressionistic, particularly those from the 1970s, but by the very end of his life Shilling moved into the realm of abstraction while still maintaining his interest in the figure, such as Self-Portrait (1981) and Portrait of a Girl with Corn (1986).

In a number of these later works, the figure and background begin to blend, an expectation we may have had as we progress chronologically through the exhibition – the color composition of the figure would often resemble that of its ground. The next step was simply to melt the two together.

Shilling’s transition to these more abstract works, works that contain the head of a figure in the top half of the canvas while a whole world of dreams and symbols unfurls in the bottom, may be due to his interest in the nature of dreaming and its positive effects (and probably affects).

The Ojibway Dreams series, particularly Self-portraits 1 and 2 (ca. 1985) – inconveniently not placed side by side – are large and vivid canvases with thick brush strokes of reds, yellows and browns, colours that mark Shilling’s distinct style.

Self-portrait 2, the largest canvas on display, immediately captured my attention.

In the top quarter of this portrait, Shilling meets the spectator’s eyes with black eyes of his own. Often when a figure gazes back at us from a painting, we try to read the eyes and the facial features.

I feel that Shilling misdirects us – since the eyes are black, we must turn our look elsewhere, to the halo surrounding his head and to the various symbols, objects and even a second portrait in the lower half. This is surely the dream of the painting’s title.

Last but not least, Shilling’s five-panel mural stands as the centerpiece of the exhibition.

Again turning his attention to sleep and dreams, this 30-foot mural begins with faces and wide eyes; gradually the eyes on these faces begin to close until the last panel simply drops off to grey and black.

For centuries the greatest painters were tasked with a mural; Shilling’s The Beauty of My People positions him as one of the greats in Canada in the late-20th century.

Rebecca Padgett’s abstract paintings are hung in one of the slim corridors of the gallery. These works function as reservoirs for paint squeegeed or widely brushed onto a canvas. By leaving these paintings untitled, Padgett likely wants us to not project a particular image or find some representation.

Rather, we seem to flow with the paint, imagine its consistency and the way it was brushed, as well as giving us the opportunity to meld into its final shape. The diptych with the pink, black and green globous masses should strike any spectator.

Padgett’s work should also be appreciated alongside Ontario abstract artist Rowena Dykins, an artist who held an exhibition at the AGP in 2011.

While Dykins finds her kin with the likes of Paul-Emile Borduas and Les Automatistes, a group of mid-20th century abstract painters living in Quebec, Padgett’s new untitled works resonate with the Painters Eleven, the Ontario equivalent, particularly some by William Ronald.

Both Padgett and Dykins are exemplary contributors to the contemporary abstract scene in Ontario.

In the top corridor hangs art of a different medium. Wayne Eardley was granted access to the GE facility prior to its recent renovations.

Eardley’s Caribou 1 series documents the space and the people therein. Eardley welcomes the uninitiated viewer into the bowels of GE.

What we find there are various peoples working together for a common goal, on both the floor and in the office. These digitally shot portraits give life to what is, from my perspective, this cold eerie facility. Caribou 2, coming in April for SPARK, will look more carefully at the space itself.

Eardley was on-hand to discuss his photographs with the audience. Indeed, when we view a photograph we know there is always a world that extends beyond the frame and it is these details that spectators are often keen to explore and discuss.

The opening reception on was packed with excited spectators. Opening and introductory remarks were made by Mayor Daryl Bennett, who then quickly departed, Kingfisher and Leitch.

The exhibition is undeniably positive and I hope the enthusiasm for Shilling, Padgett and Eardley continue just as strong until it wraps up in May.