A “keynote lecture” doesn’t do this event justice. Stohn Hall created a koan (a matter of public thought) on Thursday night to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Kawartha World Issues Centre (KWIC). Raging grannies, teen activists, and a Trent-full of intellectuals fell under Bayo Akomolafe’s spell during his vibrant lecture, “The Gift of the Crossroads: Agency, Responsibility and Justice in the Anthropocene.”

A “recovering professor and recovering psychologist,” Akomolafe is a polymath heir to Ivan Illich. But “heir” is too linear. Akomolafe charms the subtext off of every text, doubling down to graze the subtext’s subtext. His binary busting busts are binary busting. His eco-feminist-Indigenous deconstruction of discontent could incite transformative politics. However, if there’s no “there there,” we can still savour his trickster poetry riddling the world. It’s senseless demanding a “there.” I imagine his rejoinder: why crave there instead of nowhere?

Know/here, re-enchanted. Scrubbed clean of conditioning. But he goads further to scrub dirty.

When Trump called Akomolafe’s home a “shithole country,” the Nigerian retorted “[w]e are a shithole country, but I would rather be backwards than be ‘developed’ at the edge of a precipice. Better to embrace my shit than to be estranged from it.” He urged Trump to “get in touch with his shit.” Recovering psychologist indeed.

Akomolafe focuses on re-enchantment, unlearning habituated conventions to sow co-emergent connection. He resists cataloguing “things” and “beings.” They are not separate. He held up a piece of paper, invoking Thich Nhat Hanh’s query, what’s this made of?

Loggers… water… Monsanto. Everyone who touched the paper. It’s rhizomatic. Everything’s entangled.

In Yoruba nature-based religion, everything is “part of a parliament of being and becoming.” Animals and humans spill into each other, territories and boundaries “perform a sexually intimate act of losing themselves into each other.” This messy world, like paper, is made of unseen things. Akomolafe calls this a hauntological paradigm: we are made of and haunted by invisible things.

“Your body is made up of dead things. Your car is filled with dead things. Bones and blood of dinosaurs. Oil. Ancestors of different kinds.” A hauntological note found in a handbag: “I am a Chinese prisoner beaten to make bags. No food. No water. Please help.”

Power is de-fracted, distributed. Humans are decoupled, with identity and cognition torn apart. “We are being composted.” More shit, doubtless made of stardust, a mechanistic world refusing stardust and shit shine, desacralized to “biochemical mental events.”

Akomolafe disrupts climate activism, noting that when we lean against something, it’s imprinted on us. “Isn’t it queer,” he asks, “that climate change calls into question the very act of responding to it? A monster has come to eat up what we do, even what we do to solve it. Weird!”

Akomolafe lives in Chennai, India, a city facing a near-apocalyptic water crisis, yet he calls climate change “anorexic, impoverished.” Weird indeed. He finds solace in demise. But not what your grandfather called demise. There is no limited Bruce Cockburn “kick at the darkness until it bleeds daylight” binary for Akomolafe. He embraces the darkness, as “shadows have their own imperative, own weight, own epistemology, calling us to sit still.”

Stillness envisions new paths. “Everything we throw at climate change becomes part of the monster.” It’s not “merely a stubborn problem awaiting a progressivist Bill Gates-ian solution. This eco-crisis is bigger than timelines.”

Not “clock tarmac time” but “messy circular time” where the 2030 climate deadline isn’t the future: 2030 has already happened. The “1622 Indian slaughter” was/is 2030. Same with Hiroshima, the execution of Ken Saro Wiwa.

Groovy. Weird.

The Anthropocene is a mug’s game, humans outside, not entangled with, the world. Akomolafe wonders if it’s “a disguised way of trying to control and assert our permanence behind cute sounding words like ‘sustainability.’”

Echoing Achebe, he embraces “things falling apart, the most critical theme of our time” in “a relational metaphysics that speaks of a messier, mangled world—one that deprivileges ‘progress’ as a foundational ethic and political impulse.”

Akomolafe closes with Yoruba trickster Esu at a crossroads “squar[ing] the idea of forward-marching. We should not go forward” but “go awkwardly, limping with more affinity with the earth.”

What’s at stake in this woozy refraction of space and time? The world or mere words? It’s the footnote warrior’s curse, the university’s quandary. Bayo Akomolafe’s talk was Trent at its best, multidisciplinary with a hint of psychedelia, daring and global, with Stephen Stohn boldly noting “[o]ur role is to save the world.”

For Bayo Akomolafe, that involves losing it first.

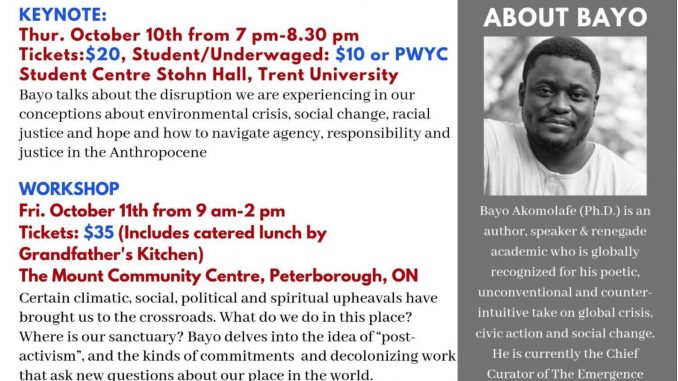

where the Kawartha World Issues Centre (KWIC) hosted Akomolafe’s keynote lecture on

October 10 as part of KWIC’s 30th Anniversary celebrations. Photo courtesy of KWIC.