On December 27, beloved local art gallery Evans Contemporary posted a statement to their website announcing that as of January 1, 2019, Evans and its sister galleries, Star X and Coeur Nouveau, were to close their doors. With this news, came the announcement that “Evans Contemporary and the Ad Hoc Arts Committee will cease to organize and present the First Friday Art Crawl.”

The statement goes on to provide further explanation of the sudden closure, citing an ethical dilemma as its cause: “… by staying in place we are in a sense enabling the gentrification of Peterborough through the use, and abuse of the arts. We fear the potential damage which First Fridays could cause, and are aware of its conceivable move in the direction of the art crawl of Hamilton, that is to say, the exploitation of art in order to focus on commerce.”

Evans and the First Friday Art Crawl meant a lot of things to a lot of different people. While the news of this closure is deeply upsetting, it must not be viewed as an isolated tragedy.

The closure of Evans Contemporary has to be viewed in the context of a tangible shift being felt in the downtown core over the past couple years. Whether it’s the Spill, Christensen Fine Art, the Pigs Ear, or Catalina’s, spaces for art and artists – of any kind – have been boarding up their windows and shutting down. And while each closure has its own justification and complexity, there is surely cause for concern.

Especially when you look closely at what the statement actually says. Paolo Fortin, Director of Evans Contemporary, felt that the First Friday Art Crawl was contributing to the gentrification of our city. He makes specific mention of the gallery’s location in the Commerce Building, owned by local real estate mogul, Paul Bennett. He urges patrons of the gallery to contact their municipal representatives regarding their concern over the gallery closures and the gentrification of Peterborough. The statement says a lot, and in few words.

But if you’re going to take anything away from it, it should be that the closure of Evans was not a financial decision. It was an ethical decision. A political action. And of course, a political action that was about much more than any single gallery. Desperate times call for desperate measures. And these are certainly desperate times.

There seems to be a consensus amongst the members of most arts communities in Peterborough: the perception of Peterborough as a unique city steeped in arts and culture is at risk, if it’s even still true at all.

In an interview with Arthur on the state of art in Peterborough, Jon Lockyer, Director of Artspace, said, “It’s a complicated time for Peterborough because we’re a community that’s very much steeped in the arts, but I’m not always sure how connected those different and somewhat disparate communities are… It’s important [to be aware of] what’s happening to everyone, because it’s usually a barometer of what’s happening across the board.”

So if spaces for art are closing at an alarming rate, what exactly is happening across the board? Unfortunately, this question isn’t answered with ease. There are no shortages of challenges that artists and arts organizers face in Peterborough.

In speaking with Ann Jaeger, local arts and culture advocate and writer of TroutInPlaid.com, I came to understand how artists are affected by Peterborough’s housing crisis. In a city with a 1.5% vacancy rate, it is increasingly difficult for low-income artists to live here, not to mention the implications on finding space to make and showcase art.

So not only must artists contend with the ever unaffordable housing market in Peterborough, but they also must do so with very little support from their municipal government. Compared with other cities of its size, Peterborough almost invariably falls short in terms of arts spending. Not only does the city fail to offer any individual grants or financial support for local artists, but it is even hesitant to fund well-established arts institutions in the city.

Lockyer noted that while Artspace receives funding from all three levels of government, it wasn’t so easy to get there: “Municipally, [adequate funding] was definitely an uphill battle. When I came to Artspace in 2014, we were at the tail end of a really long process that several directors before me had been in negotiations with the city of Peterborough to increase our funding to a comparable level with our provincial and federal funding… It’s hard to get stable and reliable funding at the municipal level.”

This funding allows the organization to pay its artists and employees in accordance with industry standards. It also means that Artspace doesn’t have to question whether it will have to close its doors anytime soon, ensuring that it remains a fixture in our community as it has since 1974.

But not all artists and directors feel the same about public funding, and while Jon Lockyer doesn’t feel that it interferes with the autonomy of his gallery, he understands why some artists take issue with the constraints that public funding could impose.

Local artist Karol Orzechowski, also known as garbageface, knows the complexity of this issue all too well, pointing to pros and cons in all sources of funding: “There’s nothing wrong with municipal or provincial funding per se — I’ve gotten different funding for different projects I’ve worked on and sometimes it’s been a godsend.” But he also notes that trying to appease people in order to receive funding can also feel like “death by a thousand cuts” which is why Karol finds a unique form of freedom in being unfunded: “When you have nothing, you don’t have to ask anyone permission to do anything.”

However, regardless of whether you’re a starving artist or contributing your music to steak commercials, Karol makes it clear that “it’s really important for artists to think about where their money is coming from and what that relationship implies.”

In talking to Paolo Fortin of Evans Contemporary, it is evident that this notion is at the forefront of all of his decisions regarding the gallery, particularly its intended role and structure as an autonomous, negative profit gallery.

Paolo Fortin was born and raised in this city, and like most artists native to Peterborough, he left to pursue greater opportunities elsewhere. Twenty years later, well into his career as both an artist and an art installer, Paolo was looking for a change of scenery and bought a home in the historical Peterborough avenues. It didn’t take long for him to realize that the arts scene had changed very little in his absence. He had hopes that someone would have opened another gallery, but came to the conclusion that “instead of waiting for someone to open a new gallery, it was time to do it myself.”

And so, in 2012, Evans Contemporary was born. In its early days, the gallery operated out of Paolo’s home in the avenues. But its domestic domain did not impede its ability to attract locals who were intrigued by the unique space and the art it was home to. Evans was an immediate success.

Paolo had come up with a model that allowed him complete autonomy as Director of Evans, a model he would call – somewhat satirically – ‘negative profit’: “the term comes from the idea that we kind of were an amalgamation. We were not a commercial entity, but we would sell. We were not an artist-run centre, but it’s run by an artist. We’re not really a museum, but we have a lot of pieces in our collection that we did display every once in a while in group shows and whatnot. It was kind of a new model, that didn’t really fit anything.”

The gallery had no public funding, and was paid with Paolo and his partner, Patricia’s money. There was no board of directors, no bureaucracy, and all the autonomy. In opening Evans under this model, Paolo made a political decision to choose autonomy over profit.

For Paolo, it was always about the art. In 2016, when the gallery moved downtown to the Commerce Building, it was because Paolo wanted moved beyond the barriers imposed by its out of home operations.

Operating out of the Commerce Building initially allowed Evans Contemporary to grow its success. Eventually it became nationally, and internationally acclaimed, putting Peterborough on the map in the sphere of contemporary art.

And while art has always been Paolo’s main focus, he quickly became involved in community building. A couple years in, Evans began showcasing local artists, providing a well-needed space for local contemporary art. In response to recent closures of various local music venues, Evans stepped into the role of trying to provide space for music, music that didn’t quite fit in local bars. All of the tips raised by the bar at music shows and art crawls, went to the local YWCA women’s shelter, raising over $10 000 by the time the gallery closed. Paolo had even begun offering residency to local artists, and in August of 2018, Karol Orzechowski, staged a month-long takeover of the space, called ‘Quality of Life’, meant to discuss issues surrounding poverty and gentrification.

In 2017, Paolo, Ann Jaeger and their Ad Hoc Arts Committee began organizing an art crawl that would take place on the first Friday of every month, quickly becoming a keystone of arts and culture in Peterborough. The First Friday Art Crawl attracted people from all demographics, bringing people from many different communities together in a space to appreciate good art – free of charge. It Ann Jaeger’s words, the First Friday became an opportunity for community members to gain education by bringing in art that people in Peterborough hadn’t had access to previously. It united people with forms of art they might have never come in contact with.

And Paolo agrees: “I wanted to show really great art, and then it was showing great music eventually. But it was always about the art, which is the most important thing to remember. We were subversively providing education – whether people were aware of it or not.”

So what went wrong?

If you ask Paolo, it all started when Paul Bennett of Ashburnham Reality bought the building from Jim Braund in 2017. This gave Bennett the perfect opportunity to declare his unwavering support of the artists who inhabited the space, saying he would ‘never, ever’ evict them. But what happens when they leave because of you’re the one who owns the building?

Because what Paolo Fortin didn’t write in his original statement, is that Evans Contemporary and its sister galleries left the Commerce Building because of Paul Bennett and big real estate companies like Ashburnham Realty: “If someone asked me, ‘if Jim Braund still owned the Commerce Building, would Evans Contemporary still be open?’ And yes, it would be. Jim Braund let the artists run the show. It felt like the artists owned the building. That’s where we get back to the idea of autonomy. Once it sold, everything changed.”

Ann Jaeger discussed these difficulties, saying, “Right from the start, we were happy to work with the new landlord as an artist group, involving all the artists in the building.”

“There are lots of capital grants for artist spaces at all levels of government, but he would never commit to that,” she explained. “That left us with the problem of having no way of knowing if he might move a vape shop next door, or move in a designer, and call it an ‘arts hub.’”

It seemed that for Paul Bennett, support of the arts stopped at simply not evicting artists.

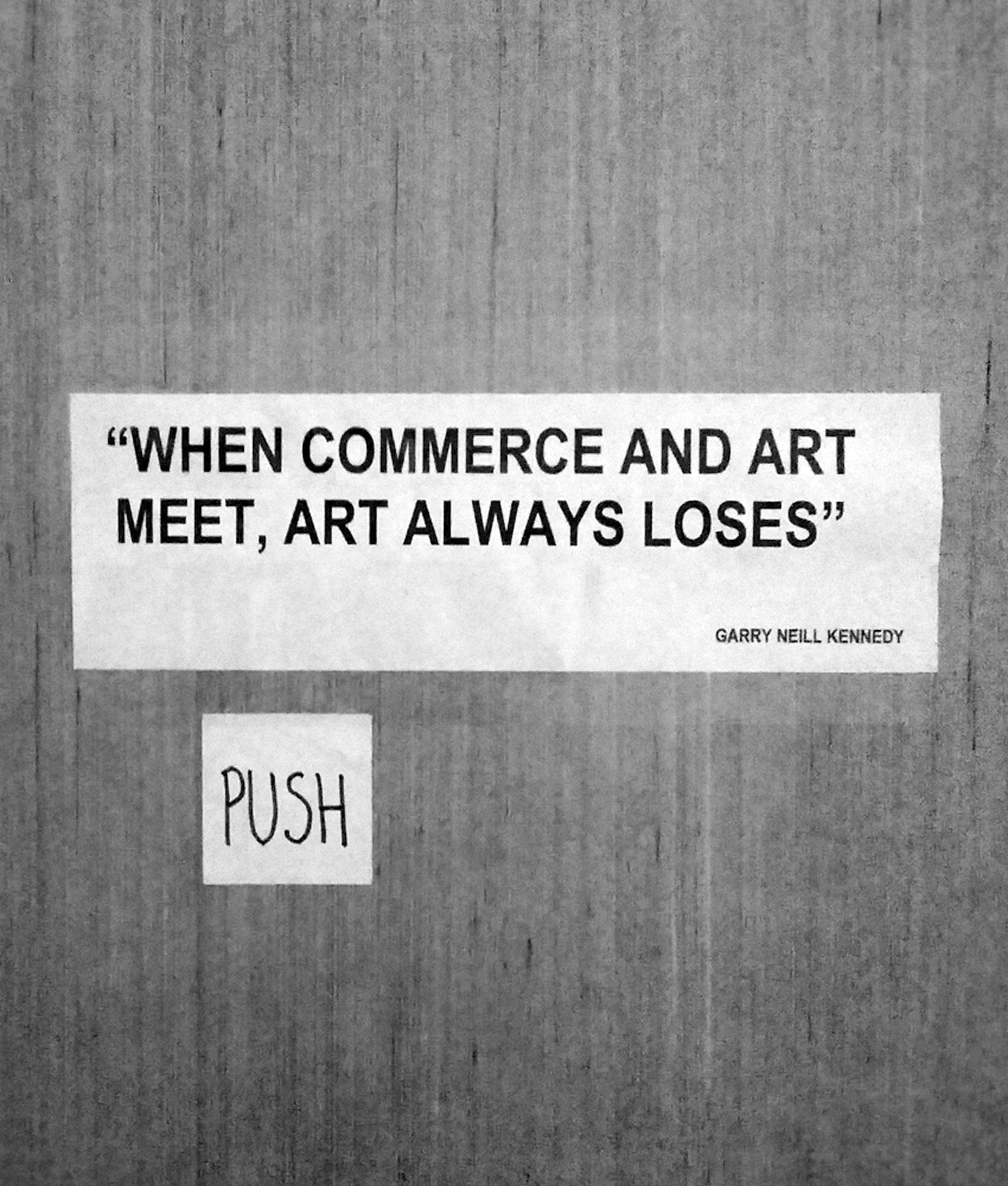

Paolo says that Bennett “has an interest in keeping the arts in the building, but not for the arts, for money’s sake. Art is good for business.”

But it wasn’t just Paul Bennett, Paolo started getting blowback from other business involved in the crawl who wanted printed maps and better signage, who wanted to brand the Art Crawl differently than the Ad Hoc Arts Committee’s had envisioned.

It had gotten to the point where the DBIA (chaired by none other than Paul Bennett) had become involved by providing modest funding for the crawl and filming its success as promotional material, leading to the perception that the crawl belonged to developers and not to artists. Paolo had to ask himself an important ethical question: did he want money from the DBIA?

For Paolo, it has always been about art and autonomy in art: “when the crawl is becomes an economic thing. When it’s about commerce, and not art anymore, that’s where I have a problem.”

Which brings us back to a point that Karol Orzechowski made quite clear: “Each individual artist is entitled to have their own ethical lines around how they participate and how they mix commerce with their own art, but as a community of artists, I really hope that we are striving to not be in service of commerce.”

So Paolo decided to close the galleries and dissolve the First Fridays before it could morph into something entirely indistinguishable from its roots in self-determination and community: “Opening a gallery is a political act. I would have to say that closing one is too.”

Which is why the announcement that the First Friday Crawl has been ‘revived’ – in part – by the DBIA feels so insidious to those who know the details of why it was in jeopardy in the first place. Suddenly the story becomes about an overwhelmingly fast community response and not about the gentrification that forced its initial discontinuation. What about the economic interests behind its resurrection? How can it possibly be revived by the people who killed it?

The loss of Evans unequivocally leaves a hole in the city’s arts scene. Things are looking bleak, and to members of the arts community, the revitalization of the First Friday Crawl might appear to be a beacon of hope.

But to those who are aware of what’s going on behind the scenes, it is quite the contrary.

But of course, one last glaring question lingers. What can we do?

We need to come together as a community and urge our municipal government to stand with artists in supporting local artists on an individual basis, as well as investing in the future of arts through funding for spaces where art can be showcased. In an ideal Peterborough, Paolo would like to see an autonomous building that consisting of two galleries, studios, a residency, a venue for music, and a café.

We also need to urge our municipal government to say no to big developers in any way that we can – even the ones who paint themselves as supporters of the arts – to ensure that we don’t wake up one day to find that our community looks a lot more like a suburb of Toronto, than Peterborough. In the words of Ann Jaeger, “when one developer owns most of the main part of the city, as a citizen, I’m concerned about that.”

If we care about the future of art in Peterborough, we need to ask our government to imagine a city that is friendly to artists, not just real estate developers.

But the most important thing we need to do as a community, is support local artists, their autonomy, and spaces that exist to benefit them – while they’re still here. And no one has said this more perfectly than Karol: “there’s always cause for concern, but it seems the only time we really talk about it is when a venue shuts down or something bad happens. It’s good that we’re having these conversations, but they only seem to happen when people are feeling nervous. When everyone is trucking along, no one stops to think about the future. That personally drives me nuts.”

“We’re at a juncture where the arts community really needs to decide if we’re going to work with real estate developers to ‘get it while the getting is good’ or whether the arts community is going to actively resist the gentrification of the downtown. There are a lot of things in play that are not in our control, but what is in our control is how we participate.”

And while it’s easy to be pessimistic about this struggle, Paolo offers some optimism: “I don’t see Evans Contemporary as being closed. I don’t see the Ad Hoc as being done.”

“The beautiful thing about art is that you don’t actually need any money to still do art. You can make art out of anything. Even to display it, you could set up a tarp in some unused alley.”