Ontario’s Lake 226 is famous. You may not have heard of it, but what has happened at Lake 226 has had an effect on Canada’s environment and on environmental policies in many countries.

Ontario’s Lake 226 is famous. You may not have heard of it, but what has happened at Lake 226 has had an effect on Canada’s environment and on environmental policies in many countries.

Lake 226 is part of the Experimental Lakes Area (ELA), a world-renowned freshwater research centre run by the federal government near Kenora, Ontario. This past May, the government announced that it is getting out of the ELA business, leaving many wondering what the fate of ELA will be.

According to statements made in June, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) director-general David Gillis said it was possible that universities or “interested parties” could take over as operators. There is no word yet as to whether or not anyone has plans to step up to take over ELA.

In the 1960s, the Canadian and American governments were concerned with the eutrophication of the lower Great Lakes. Eutrophication is a process whereby nutrients enrich a lake to a point that plants and algae grow aggressively, lowering oxygen levels, and potentially creating toxic algal blooms. The problem was, however, that no one knew for sure which nutrient to blame.

The ELA was created in 1968, allowing scientists to perform whole lake experiments to understand eutrophication. Shortly thereafter, a study in Lake 226 showed the world that phosphorous was the limiting nutrient in lake systems-the abundance of which caused eutrophication.

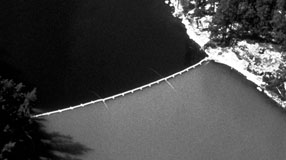

You may have seen the famous photo of Lake 226-the lake is split in two by a plastic curtain, one half of the lake clear, the other half, containing phosphorus, is a sickly pea green. If you’ve taken a limnology or environmental studies class, chances are there is a photo of the lake in your textbook.

The aerial photo of the experiment became “world-renowned,” wrote David Schindler of the University of Alberta, in a piece regarding ELA in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. “It had more impact on policy makers than hours of testimony based on scientific data, helping to convince them that controlling phosphorous was the key to controlling the eutrophication problem in lakes.” Schindler, formally of Trent University, helped conduct the experiment on Lake 226 and was the founding director of ELA.

Governments moved quickly and banned high levels of phosphorous from laundry detergents and many ensured that phosphorous was removed during sewage treatment.

Since then ELA, which is home to 58 lakes, has been instrumental in studies regarding acid rain, hormone levels in water due to pharmaceuticals, the effects of various toxins to fish and the environment, greenhouse gases and more.

There has been over forty years of research at ELA, as scientists from around the world and from different disciplines come to the outdoor laboratory to test theories and learn from each other. To Steven Bocking, Professor and Chair of the Environmental Resource Sciences/Studies at Trent, ELA is different than traditional laboratory-based science, as it creates “a kind of community or a social ecosystem.” It brings “together a bunch of scientists and their students in one place so that they can share their information, share their ideas, and talk about joint problems and collaborate, and do all that kind of connecting stuff that is central to doing science.”

But DFO will no longer be footing the bill ($2 million annually) for ELA come March 2013, due to changes to the Fisheries Act in the 2012 Budget, and despite outcry from scientists, prominent international scientific publications, and groups like the Coalition to Save ELA. Pressure has increased lately, as several Liberal, NDP and Green Party MPs stood up in the House of Commons this month and presented petitions asking for ELA to remain open.

On October 18, the Coalition to Save ELA proposed that Environment Canada (EC) should take control of ELA, as it has long been involved with ELA and ELA would, they argue, fit into EC’s mandate. ELA could “assist the oil and gas industry in managing risks… [and] be used by EC to determine the fate and effects of chemicals found in diluted bitumen in pipelines and oil sands tailings.” But according to a statement given to the Globe and Mail by a spokesperson for Environment Minister Peter Kent, “the answer is no.” This comes only nine days after Minister Kent announced that EC would be spending $16 million over four years on the new Great Lakes Nutrient Initiative that “will advance the science to understand and address recurrent toxic and nuisance algae in the Great Lakes.”

It’s not over for ELA just yet. It is possible that the government could reverse its decision, or that a third party steps in to fund the program. The scientific world is watching Canada, waiting to see what will happen to the unique Experimental Lakes Area.