The quest of identity has long since been undertaken by scholars and individuals alike. While some may have better clues as to who they are than others, there is certainly no absence of effort to close the gaps of information. That is precisely what Dr. Katrina Keefer aims to accomplish, as she made clear in her lecture on identifying African tribal marks and scars on documented slaves. With an attendance of 18, the lecture offered valuable information to those with a passion for history and anthropology alike – despite the atrocious weather and road conditions that evening.

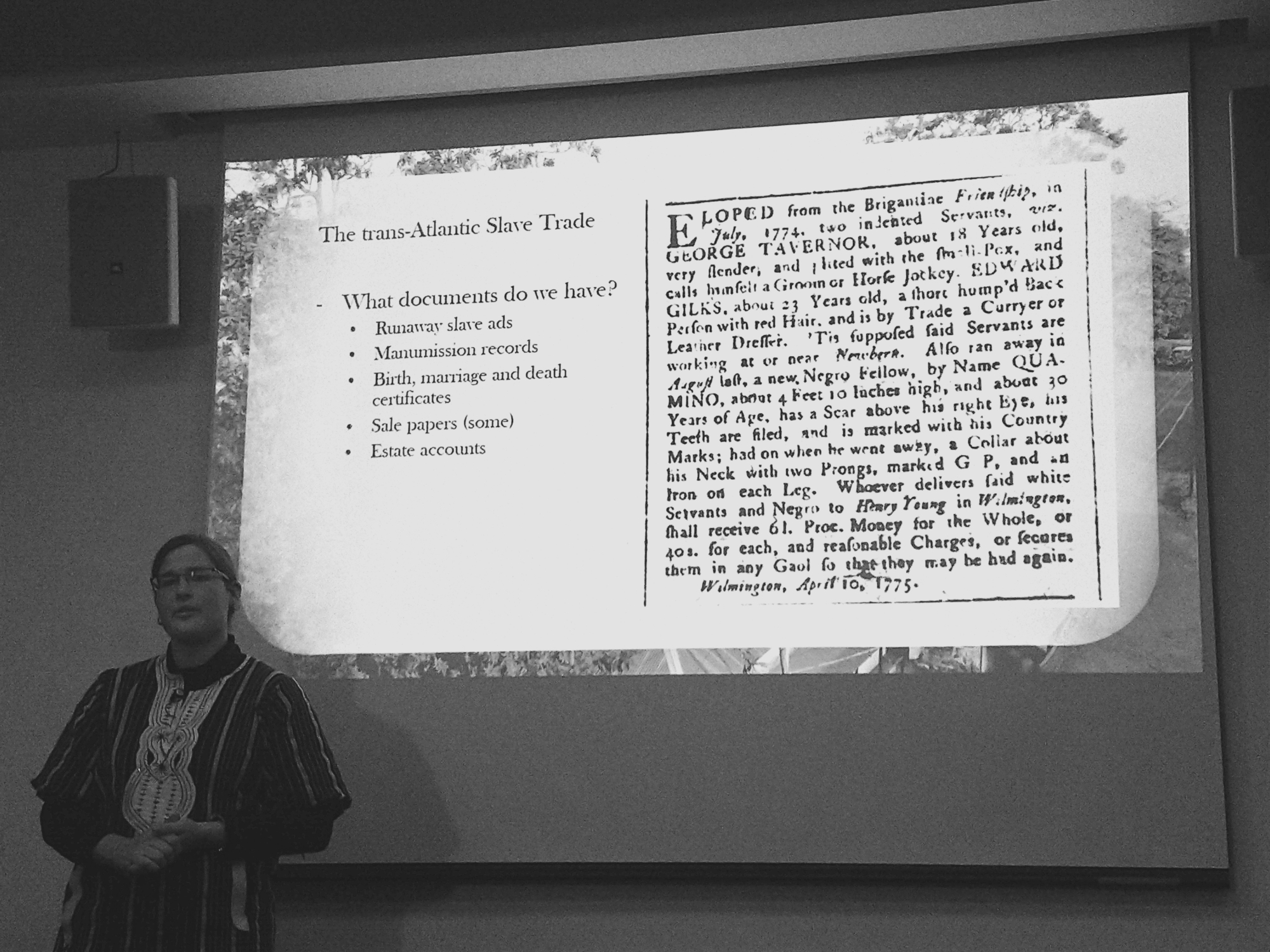

The lecture began with a briefing on the concepts of identity and a summarized history of the slave trade. The route maps of the slave ships and their destinations, served as some of the primary evidence that Dr. Keefer used to identify heritage among descendents of slavery. Various ports along the South American coastline and the Caribbean and Atlantic States were such examples. The different ethnicities of the 10.7 million slaves (out of 12.5 million) that survived the treacherous voyages aboard those ships were symbolized by their body markings, piercings, and other physical features. She cited many different examples of markings found in (recently uncovered) logs and historical documents – such as the Register of Liberated Africans (of which has over 100000 entries, and almost all up until 1827 include textual descriptions of marks, to date) in the Freetown Peninsula, Sierra Leone – and tied it to living individuals deriving from that lineage – dating back to well around 300+ years. The register itself is one of the key resources in the ongoing project – of which Dr. Keefer has quoted to be “a life’s work” – in uncovering the lost identities of the slaves.

The injustice of losing one’s identity and history is what inspired Dr. Keefer’s work and progress, of which she mentioned is also shared by the MATRIX at Michigan State University, which is a centre for digital humanities resources. The site is creating a system that allows marks and other physical features to be parsed like a code, and translated into a documented identity pattern – which of course saves a lot of time compared to scavenging for hundred-year-old logs and records, but these historical contents are undoubtedly essential to the systems ultimate goal of creating its database.

In addition, she went into detail as to what these marks and scars meant to those who wore/bore them. Many tribes signified various aspects of their lives through them; from the bonds of their people to their feats of accomplishment.

With that in mind, we cannot forget that history has a cruel reputation of forgetting itself. Many descendents of slaves were born without receiving markings or any other sense of identity, especially those born in the American colonies and states. Not to mention, the gradual cultural and ideological assimilation forced upon many slaves leading up into their emancipations further stripped them of their identity. Keefer said, “marks place us in time, space, and community” – no doubt an attestation to the unique conventions that define the human ‘being’ within that respect.