France, 1944: Absent of rest and with minimal supplement, a young medic has been ferrying casualties from the front line for over 48 hours. Stubborn and determined to minimize his losses to the reaper, he presses on. Nearly losing control of the field ambulance from exhaustion and the winding roads of the French countryside, his partner persuades his absence from the driver’s seat.

France, 1944: Absent of rest and with minimal supplement, a young medic has been ferrying casualties from the front line for over 48 hours. Stubborn and determined to minimize his losses to the reaper, he presses on. Nearly losing control of the field ambulance from exhaustion and the winding roads of the French countryside, his partner persuades his absence from the driver’s seat.

He sluggishly walks around the vehicle and collapses into the passenger seat. As his friend since basic training places the truck in gear, a round from a German sniper makes contact with his forehead. The cab and its surviving occupant are instantaneously turned a different colour. After the war, unable to live with the horrors he beared witness to, the medic returns to Canada where he takes up the drink. The medic was my great uncle.

Malcolm Naismith, my great uncle on my mother’s side, whose name is scribed into the new addition of the Peterborough Cenotaph, was an aircraft technician during the war stationed at CFB Gander. Eager to head overseas, he submitted papers to become a fighter pilot. Thankfully for my great aunt, but with much personal disappointment, the war ended before he could make his acquaintance with the Luftwaffe.

My grandfather, from whom I derive a large part of my inspiration, was also an aircraft technician in the RCAF seeing postings in Germany, France, Britain and Italy.

When I was eight, he took me to my first air show at CFB Borden. With schoolboy impressionability, I watched an F-15 Eagle not ten meters above the forest canopy approach at an outrageous velocity. Flirting with the sound barrier, in a halo of condensation, the pilot suddenly took to the vertical, propelled into the clouds by those thunderous cones of flame called afterburners. I made the decision in that moment to join the military.

The family stories and exposure to all things martial were rare and fleeting during my life. I was never certain when those moments might show, so when they did occur, I greeted them with enthusiasm and attention.

Like many young children, I played Army with plastic soldiers making sound effects with such startling accuracy, Michael Bay would blush. I built model airplanes and had picture books about various ships, aircraft and tanks that I would read into the wee hours of the morning. As I began to age into a man, I felt I understood enough about the GAU-8 30mm cannon on the A-10 Warthog and branched to history.

The more I explored, the more apparent it became that we are indeed immeasurably fortunate. It has never ceased to impress, the level of unflinching commitment in the face of incomprehensible danger our men and women have demonstrated to defend our freedom.

August 19, 1942: A flotilla of amphibious transports approaches the French coast. Under the command of Vice-Admiral Lord Mountbatten, 5,000 members of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, 1,000 British Commandoes and 50 US Rangers put boots to ground at 5:00AM for Operation Jubilee.

When the doors fall, a wall of lead strikes men down by the dozens before they have the opportunity to return fire. Once free of the landing crafts, German artillery and mortar positions begin to shell the beach as the men scramble for cover. The muzzles of anti-aircraft cannons atop the cliffs descend towards terra firma and release flack rounds upon the allied soldiers below.

On the 60th anniversary, a veteran in an interview with the CBC said with an emotional quiver: “As soon as those doors fell, it was hell on earth.” When the retreat was sounded at 10:50AM, with no preliminary bombardment from the Royal Navy or the Royal Air Force, Canada suffered 3,367 casualties – eleven soldiers a minute. Operation Jubilee is better known as The Battle of Dieppe.

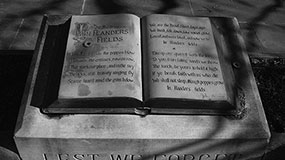

You have all sat through grade ten history. You know the stories. You know of Vimy, Passchendaele, and Juno. The Battle of the Atlantic. Korea. Somalia. Yugoslavia. Afghanistan. My interest from that moment as a budding eight year old led me to discover some incredible things about our veterans. This Remembrance Day, at the Cenotaph, I will be paying my respects to the service of my family and those who made the trivial freedom of purchasing Starbucks possible. I will stand a proud Canadian listening to “The Last Post” and John McCrae’s “In Flanders Fields.”

I did not write this piece to trumpet war as a glorious business. I wrote this piece to ask for your reverence, your gratitude and your deference for veterans. I ask on November 11 that you place a poppy upon your heart and honor “those who died, and those who dared to die but lived.”