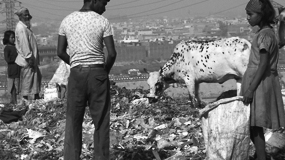

Amy Miller is a veteran of the ReFrame Film Festival. She is returning to the festival this year with her film The Carbon Rush which explores the lives and stories of people affected most intimately by carbon-trading. The film brings to the forefront their experiences as a way to shine light on the actual effects of projects started under the Kyoto Protocol and the United Nations Clean Development Mechanism. It will be screened Friday, January 25 at 4:45 pm at Showplace.

Arthur sat down with Miller to discuss filmmaking and social justice.

How long have you been a filmmaker?

This is my sixth year. I started in 2007 and my first short was ReFrame, and my first feature was at ReFrame as well. And now here it is with The Carbon Rush. So it’s been really great to be able to share my projects with ReFrame and I love the festival. The programming is incredible and it’s such a nice mixed community of people engaged in social justice and the artistic community.

How did you get involved in ReFrame originally?

I was in Peterborough for a few months and when I moved back to Canada after shooting Myths for Profit and during shooting I got to know people involved in the film world and ReFrame, and a lot of different people spoke highly of the festival. I submitted my [film] to the programmers and I was selected. That was 2009.

Do you think that festivals are the best way to address these kinds of issues? Do you think this will compel people to take a second look at environmental issues?

I would reframe your question to say “is there a usefulness to the festival?” and the answer is absolutely yes, but there’s no one best solution. There’s not gonna be one documentary that turns people into revolutionaries or activists, but what they can do, as Paulo Freire said, is that we can develop tools so people have those “a-ha” moments where all of a sudden they can connect the dots and see the relationship between themselves and the rest of the world and the situations they’re in. […] So with a film like The Carbon Rush it’s not going to necessarily turn people into super-climate-justice activists, but it could help them connect the dots of system of powers that exist in the world, and that’s just one piece of the puzzle. People have to get their critical analysis in a multitude of ways but it also has to be done in a praxis of action. So I definitely think having the film in the festival is fantastic in that there will definitely be a positive aspect to it.

Why do you think art and social justice tend to go together?

I think that language’s essential connection is pretty loaded. I think people can respond to art in so many different ways. In the last 100 years we can definitely see where the fusion of transformative social justice with any sort of medium that is called art has an impact. There’s definitely a historical line. I think it’s because there’s a usefulness. We’re trying to convey messages and art in all its forms can do that.

How did you get involved in filmmaking with a political science degree?

Well, my background as an organizer. I’m not trying to make films, I’m trying to make popular educational tools and I think documentary is a great format to do that. Whereas a lot of filmmakers are caught up in these conceptual ideas and this idea of art as expression, for me it’s more about developing critical analysis. So I tackle filmmaking from an organizer’s point-of-view on how do you take a project from A-Z. For me it’s about producing and results, so I just started doing it and asking anyone I knew who had made films for advice, I did a couple workshops here in Montreal. I think if you’re going to learn about making film, you just start doing. That’s the whole basis of popular education—it’s not about infusing yourself with knowledge, it’s about acting through it.

What do you have to say to students who want to do these sorts of projects?

There are people who talk about wanting to do these sorts of projects and then there are people who do. It’s not a question of having cash or connections or not, it’s do you want to make a film or not? If you want it you can make it happen. You have to be innovative and you have to be tenacious. That to me is what’s going to make the difference of whether you make your films or not. It’s not about whether you went to film school or not. No one’s going to ask if you went to film school. What people are going to ask is “what did you last make?” If people want to do it, that’s how they’re going to get better. I’m not discrediting going to film school, but whatever you can do to work on your projects, you will get better.

Would you say this also applies to the dilemma a lot of students are having where they graduate and feel like they can’t get the job they want?

I think the capitalist system we live in in North America is soul-breaking and backbreaking and that there’s a hard economic reality where people don’t get to work on their projects because they have to work two or three jobs to feed their family and pay their rent despite having dreams and desires. It’s horrible that there’s a lot of young people who get out of university super laden with massive student debt and they’re not in a position to learn their craft or make a bunch of mistakes and figure it out. There’s definitely a level of privilege and realities of what it takes to get experience. But there is an element of character as well. It’s going to be difficult to make your film happen if you’re lazy. It’s a combination of a lot of things, but I definitely wouldn’t say that all the people that are unemployed are that because they aren’t ambitious enough. It’s really hard with all the structures put in place.