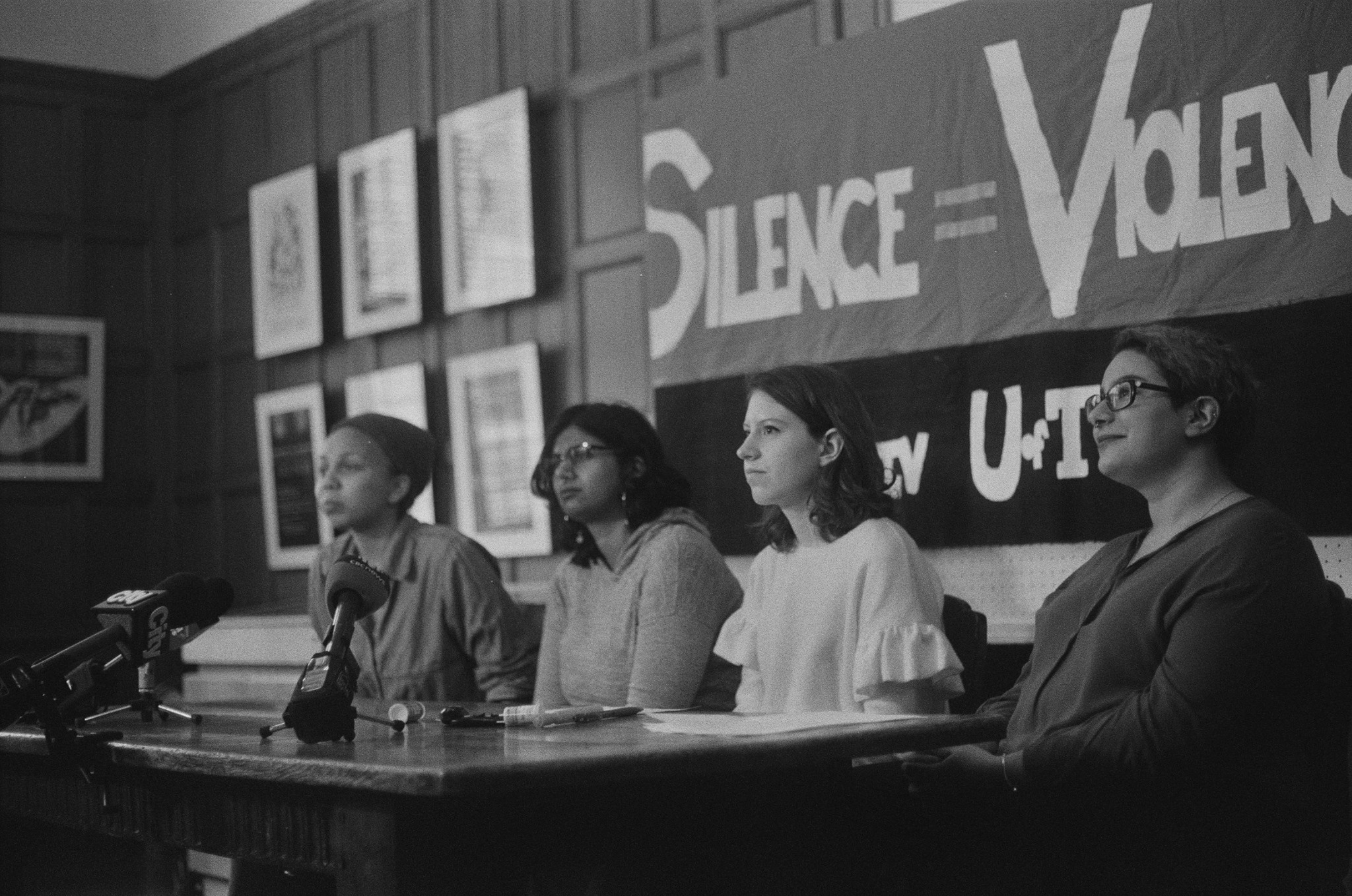

Photo: Tamsyn Riddle sits second from the right at her Silence is Violence press conference at Trinity College at University of Toronto in April 2017. Photo by Hannah Dos Santos.

In April, Tamsyn Riddle filed a human rights application against U-of-T for inadequately handling her 2015 sexual assault case against another student.

Riddle is a University of Toronto (U-of-T) student from Peterborough. She is currently in her fourth year of undergraduate studies in Diaspora and Transnational Studies, minoring in Equity Studies and Political Science. As an Arts and Science student, Riddle is a member of Trinity College at U-of-T’s St. George campus.

The university’s process for handling cases such as Riddle’s fell under the Code of Conduct. She notes this itself was an issue: “The Code of Conduct is mostly used for roommate disputes and vandalism, things like that. Not violence.” In the process, the university investigates the student’s complaint; implements interim measures; and then decides whether to move towards a hearing. If a hearing is held, the hearing’s decision stands. U-of-T’s investigation of Riddle’s case ended in September 2016, spanning 17 months in total.

“They took a really long time with every step,” she says, noting that the investigation process alone took four months.

She also details that the interim measures in place for the perpetrator were poorly executed. For example, the university and college allowed the perpetrator to move in early, do training, and be a Frosh week leader in 2015. As well, the measures regarding the perpetrator’s involvement in the college community were vague enough to be contested, or not upheld at all.

“They imposed interim measures where he wasn’t allowed to eat in the dining hall and participate in clubs, and he had to move out of residence within the next month,” Riddle says, offering more examples. “He would eat in the dining hall anyways. No one would enforce it. And he stayed living in residence longer than he was supposed to.”

According to Riddle, the university then went quiet during the earlier part of 2016.

“In January 2016, I was told they were doing further processes, and that there would probably be a hearing before April,” she says. “I didn’t hear anything for nine months.”

After this extended period of silence, U-of-T closed Riddle’s case, having settled the case between the university’s and the perpetrator’s lawyers.

“In September, pretty abruptly, I got an email saying, “Can you meet tomorrow?!” from the Dean of Students,” Riddle continues. “[The perpetrator] was allowed to pay his own legal counsel outside of the university, because I was just a “witness” under [U-of-T’s] processes. So the two parties excluding me, without my knowledge, settled the case on these confidential terms that [the Dean of Students] paraphrased to me.”

To add insult to injury, the agreement between the university and the perpetrator was “just a more permanent, extended version of the interim measures” made more specific about the perpetrator’s participation in clubs and groups, says Riddle.

“He wasn’t suspended or anything. It was just minimizing how much I would have contact with him, but not punishing him in any significant way,” she remarks. “It was myself and another person who had been assaulted by him, so they should have done extra [because of that].”

Frustrated with the lack of justice through the university, Riddle reached out to York University activist and PhD student Mandi Gray who connected her with the Ontario Human Rights Tribunal (OHRT). The OHRT aims to resolve claims of harassment and discrimination in a timely and just manner. Through the OHRT, the two parties involved are engaging in mediation this winter. If this does not resolve the case, the Tribunal will hold a hearing.

In the meantime, Riddle keeps busy by working with student groups combatting sexual violence, which she claims has been crucial to her pursuit of justice. The two groups she works closely with are U-of-T’s chapter of Silence is Violence (SiV) and Trinity [College] Against Sexual Assault and Harassment (TASAH). SiV works across the entirety of U-of-T, while TASAH focuses on Trinity College.

“SiV defines itself as an intersectional feminist collective that does activist work around sexual violence,” she states. Riddle defines her feminism as “more about dismantling the patriarchy, and other systems of power that work alongside it, that disproportionately harm women and femmes.”

SiV does work through guerilla poster campaigns like “Survivors Speak Back,” offering resources for survivors, accompaniment to appointments and/or police stations, and critiquing the university’s quarter-hearted efforts to implement sexual violence policy. SiV also offered extensive support with Riddle’s press conference about the OHRT case held this past spring.

TASAH is “usually more focused on policy change and things like that, maybe less “activist”-type work,” explains Riddle. It does events like socials, consent campaigns, and speaker-panels.

Like Trent, U-of-T operates with a collegiate system in which students can reside during their early years, find community, and “have a home base,” as Riddle describes it. She explains further that Trinity has been having issues with sexual violence recently, particularly surrounding student politics.

“Trinity in particular is very concerned with its reputation; it has this good reputation as “the best college at U-of-T” and as a very academically rigorous place,” Riddle says. “So what [happens] if you’re being sexually harassed by the president of the college? Or the provost? Which happened, with a former provost. And he just moved on to Oxford.”

Reputation is a factor at the individual level. Perpetrators of sexual violence often have power in money or influence, Riddle explains, so they are more likely to sue if they feel threatened or unjustly treated by reprimands. This rings true for her case.

“In my experience, it never felt like [the university] didn’t believe me, which is good,” she claims. “But at the same time, it was clear that they didn’t see it as being possible for them to expel [the perpetrator], or even to have him not be part of Trinity College.”

Reputation is also crucial for universities. As schools try to achieve or maintain prestigious status, there is growing mainstream concern that universities are becoming more overtly business-like rather than academic institutions.

“The higher the prestige, the most students you can attract,” Riddle agrees. “They want to attract students. They want to show U-of-T as a safe campus, so being known for sexual violence doesn’t really lead well to that.”

“I think one of the problems is that there’s this inclination to say, “These experiences are so obviously horrible, the administration just must not know this is going on! If we just tell them, in a very rational way, and put together these statistics, then surely, they’ll just understand,”” she says with a wry smile. “The administration works the way it does. It’s a bureaucracy. It entertains people that do this and churns them through all these processes and in the end, nothing changes.”

This underscores the importance of SiV’s work for Riddle: “We’re making sure that there is public pressure, that there is bad PR, and that’s what happens when they don’t deal with sexual violence [adequately].”

Media coverage can be a double-edged sword, Riddle admits. Her case has been covered by CBC, Vice, The Toronto Star, Now, Buzzfeed, and U-of-T’s newspaper The Varsity, the last of which she is currently a regular contributor.

“I think when cases go to the media, it gets kind of exceptional-ized. It makes people think that it’s an isolated or extreme incident, as opposed to something that’s happening all the time,” she explains. “So while survivors are messaging me saying, “I relate to your experience,” I think a lot people also think that it’s something that doesn’t happen at every school.”

Still, U-of-T is no stranger to bad press. For example, Dr. Jordan B. Peterson of the Psychology faculty has made controversy within recent years for discouraging the accommodation of students’ pronouns and the adoption of trigger warnings. As a student who has experienced trauma, Riddle believes trigger warnings are necessary, especially for students who are financially unable to work through their trauma with counselling.

“It’s part of this whole rhetoric of objectivity. “Academia needs to be this place of higher thinking, and emotion just doesn’t belong there!” which is coded for “White men – who are automatically thought of as objective – are the people who really belong,”” Riddle says. “Instead of being able to be in school equally as someone who’s experienced trauma, people are punished for it. That can be retraumatizing.”

As she pushes for community justice, Riddle also tries to practice self-care. On top of classes, being in the public eye in the social media age has been a challenge.

“I feel like for me in particular, having a disability my whole life affects self-care. I can at least speak for diabetics when I say disabled women are always being told what to do,” she explains. “And I think with activist groups there’s a big emphasis on productivity. It can be hard to take a step back from that. So [self-care is] being easy on myself, and giving myself time away from things. Getting enough sleep. Also, seeking out people who understand, and setting boundaries on relationships.”

Through everything, Riddle still maintains her Peterborough roots by coming home for holidays and reading weeks. She keeps the city in mind.

“I hope if people in Peterborough are paying attention to this, people will think about their own communities and the people around them,” she advises. “Who doesn’t go to events? Which people seem to be avoided by other people? Which men are women not comfortable around?”

“I think it’s important for people who are not survivors, and men, to educate themselves to they can be a safe person for people to come to,” Riddle concludes. “Because it’s not that you don’t know survivors – it’s that survivors aren’t comfortable talking to you.”

Correction (November 14 2017): Against the print edition, Tamsyn Riddle minors in Equity Studies and Political Studies, rather than Ethnic Studies.

Web Exclusive extended content

(Author’s Note: This interview was extremely fruitful. Alas, the print medium could not meaningfully accommodate all topics discussed, despite their relevance. As a result, they are as follows below.)

On U-of-T’s updated sexual violence policy:

As a part of SiV and to see her justice through, Riddle has been following U-of-T’s attempts to reconcile their resources for sexual violence. Unfortunately, it seems again to be an issue of optics.

“There was one consultation for each campus that [U-of-T] did last summer, in June on a Thursday morning or something, so no one was around,” Riddle recalls. “They didn’t incorporate any real feedback into it, and it’s pretty much the same [as it was before] except it centralizes resources at this new sexual violence centre.”

While a sexual violence centre sounds promising as a resource, its value becomes squandered when it is not clearly available to students.

“Robarts is the [main] library, and it’s a huge and really intimidating building. For the first few months, the [new sexual violence] centre was tucked away in this building that’s in the physical building of Robarts, but separate,” she says. “It’s called the Bissell building, but no one knows what that means. It’s actually inside Robarts: you turn into this corner and you take the elevator. So it was really hard to find. Technically wheelchair accessible, but pretty questionable.”

The centre has since moved to 702 Spadina avenue.

On the word “survivor”:

Riddle refers to herself and others as “survivors” of sexual violence, which is decidedly different from “victims” of sexual violence.

““Survivors” is more of a term that’s been used by feminists and grassroots anti-violence activists as a way to reclaim the experience, to say we’re not just passive victims and to recognize the strength of people who survive violence; and shift the focus onto them being able to move forward instead of putting the focus on what happened to them,” Riddle explains. “It focuses more on them moving on however they do, and on the things that they’re able to do with that experience. So part of it is that it’s used more often by people doing anti-violence work, but I also like that focus on recognizing the strength of people and understanding it as an ongoing process of continually surviving the effects of violence, rather than just someone that something happened to. Not just being acted upon.”

However, Riddle acknowledges that there valid critiques of the term she prefers.

“There’s that trailer for The Hunting Ground [2015 documentary] where it was like, “They went from victims to survivors! Now they’re empowered!” which kind of puts the onus on survivors to act out empowerment in certain ways,” she notes. “Obviously that is easier for some people than others. Not everyone gets to be “empowered” and visibly talk about their experiences. I still think the idea of “survivors” is moving in a better direction than “victims.” But some people call themselves “victims,” and that’s okay too.”

On misconceptions about sexual violence:

Speaking about sexual violence in a public setting often means running up against misconceptions about sexual violence. Throughout her time as an activist and as a student, Riddle comments that the misconceptions are many and intertwined.

“A lot of times these myths are listed out individually, but all together, what it does is pictures sexual violence as something that just naturally happens as opposed to a result of power differences that exist,” says Riddle.

“The idea that sexual assault happens when you’re walking outside alone at night; or that certain women deserve sexual violence because of the way they dress or if they’re sex workers; the idea that sexually assaulted by strangers… But most of these put together create this very depoliticized image of sexual violence that is used more to control,” she continues, offering a non-exhaustive list. “These ideas [posit] “If you act a certain way, you will experience violence. As a result, you should protect yourself.” When in reality, most people are sexually assaulted by people they know.”

She also notes that there is a prevailing racialized myth about sexual violence victims being white women, and perpetrators being criminals, or otherwise “obviously dangerous.”

“[This] really means racialized men and disabled people or mentally ill people,” she adds. “Again, not the reality. Women of colour and people of colour generally are more likely to experience sexual violence, and perpetrators are often more powerful people. What this does [then] is reinforce the criminal justice system and the racism that it reproduces.”