2018 is slowly coming to a close and winter is encroaching. So much has happened in this quickly diminishing year, but that does not mean the conversations that began are close to over. Race and the need to understand culture have been at the forefront of social discussion for close to a decade now. There are constant struggles in Europe and North America between African-Americans (or people who could otherwise be grouped together as “black”) and the general society.

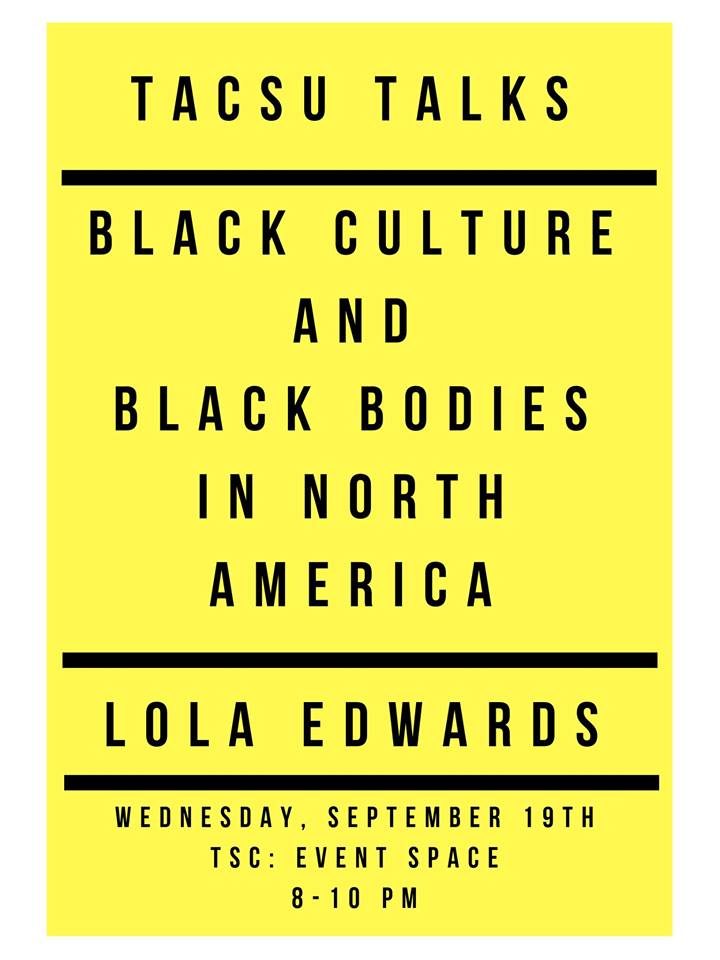

As a part of Trent African Caribbean Student Union (TACSU) Talks, a monthly guest-led discussion with members of the Trent community, questions and ideas of black culture and black bodies were introduced into the discussion in the Student Centre Event Space on September 19. Everyone had a different way of explaining and understanding what culture first is, and then what black culture is. The consensus, however, was that the definition changes depending on whose perspective we are understanding.

Although it may seem like beating the dead horse – especially following the rekindling of awareness and perhaps even over-awareness of the black body during and following U.S. President Trump’s election – it is still an important discussion that has yet to be settled.

Culture compromises of so many things internally and externally – tradition, genetics, history, geography, arts etc. As black people – whatever it is that we decide being “black” means – there is a culture that we have access to, create, contribute to, and ultimately, share. The issue today, with regards to culture, is the limited amount of autonomy that black people have over their culture. Politically, economically, socially, there seems to be an alienation of the black body from its respective culture. That is to say, black culture exists outside of the black body – and in the society we live in today, the culture is more revered than the bodies that created it. Dissecting the black art society so fervently consumes, such as Childish Gambino’s “This is America,” would reveal this unfortunate reality.

One of the great works of art and protest that 2018 has tossed into our lap is Gambino’s controversial “This is America.” What makes it so impactful is his coy refusal to explain the ideas and the context behind his work. The video and lyrics are rife with symbolism, but which symbols are meaningful and which ones are a figment of our imagination – a product of overthinking?

The video opens with Gambino in what many people interpreted to be the caricature Jim Crow shooting a guitarist with a bag over his head. If you were not paying attention before, you are now. Throughout the video there are several acts of violence, none lasting longer than a few seconds. If you look closer, after each shooting, Gambino hands the gun to a child who reverentially accepts it with a cloth in hand as though it is a sacred or fragile item. This weapon that, through news and protests, we know constantly destroys black bodies – kills them – is treated with more respect than its victims are. Conversely, we cannibalize black culture.

Gambino, whose real name is Donald Glover, is active throughout video moving through different scenes – sometimes causing violence, other times dancing. The dance moves are easily recognizable: like the Shoot, pioneered by BlocBoy JB, there are also notes of the South African dance Gwara Gwara. Dance moves that are easily recognizable to most people, moves that many people have practiced in front of mirrors, friends and on dance floors. They are just distractions to the chaos in the background, and that’s the point. As we immortalize these dance moves, memorize the repetitive rap lyrics, fetishize the rich celebrity lifestyle, we miss the point and ignore the chaos. The moves are born of culture, the lyrics powered by strife and pain, memories of the struggle-laden black experience. His video seemed to say that America – and by extension, its social and cultural counterparts – revere black culture but hate black bodies.

Take, for instance, Kim Kardashian-West’s controversial hairstyle. Earlier in the year, the reality star donned traditional Fulani braids to a red-carpet event. Many were livid, others loved the hairstyle choice. The issue does not lie in her hairstyle choice – there are many other symbolic misses that signal a certain level of culture cannibalism. When celebrities wear a certain designer – they announce it with pride, giving credit where it’s due. Kim didn’t extend the same courtesy to the Fulanis. To pour salt into the already-angry wound her children, who are black, have never been seen with any natively African or African-American hairstyles. She is not embodying or respecting the culture – she is riding the wave of a “trend.”

When an entire group of people’s culture is reduced to the triviality of a trend, issues follow. A trend, by definition, is a fashion. Fashion goes in style and goes out of style. When a culture, a history and a story that carries significance, fosters community, is the source of art and expression, and is, creates and becomes an identity for so many people becomes a fashion – it further alienates the bodies attached to the culture. Even worse, it reduces the respect for the culture and the autonomy of those who truly identify as part of the culture.

This brings us back to this idea of black culture. What is it? How do we define it and reunite it with its alienated body? By respecting it and the bodies that contribute to its creation. Our society worships at the feet of black artists, celebrities, stars. People like Kendrick Lamar, Childish Gambino, Kanye West, Beyonce, Jay Z; these are names that carry weight. Each of these people come from black culture. They might be black, but their influence and reach are not limited to their culture. Their roots, history, ethnicity, personal trials and tribulations, have branded them with something that persist beyond the short shelf life of fashion and trends. They represent a culture that exists beyond their fame and recognition. To reinstate the importance of black bodies in America and beyond, we need to reunite them with their culture and more importantly, allow them agency over it. This is a fundamental right.