The year is 1982. Pierre Trudeau is still raising his children at 24 Sussex Drive. Ronald Reagan was elected just last year; he will occupy the White House for the next seven years. The rise of neoliberalism is well underway.

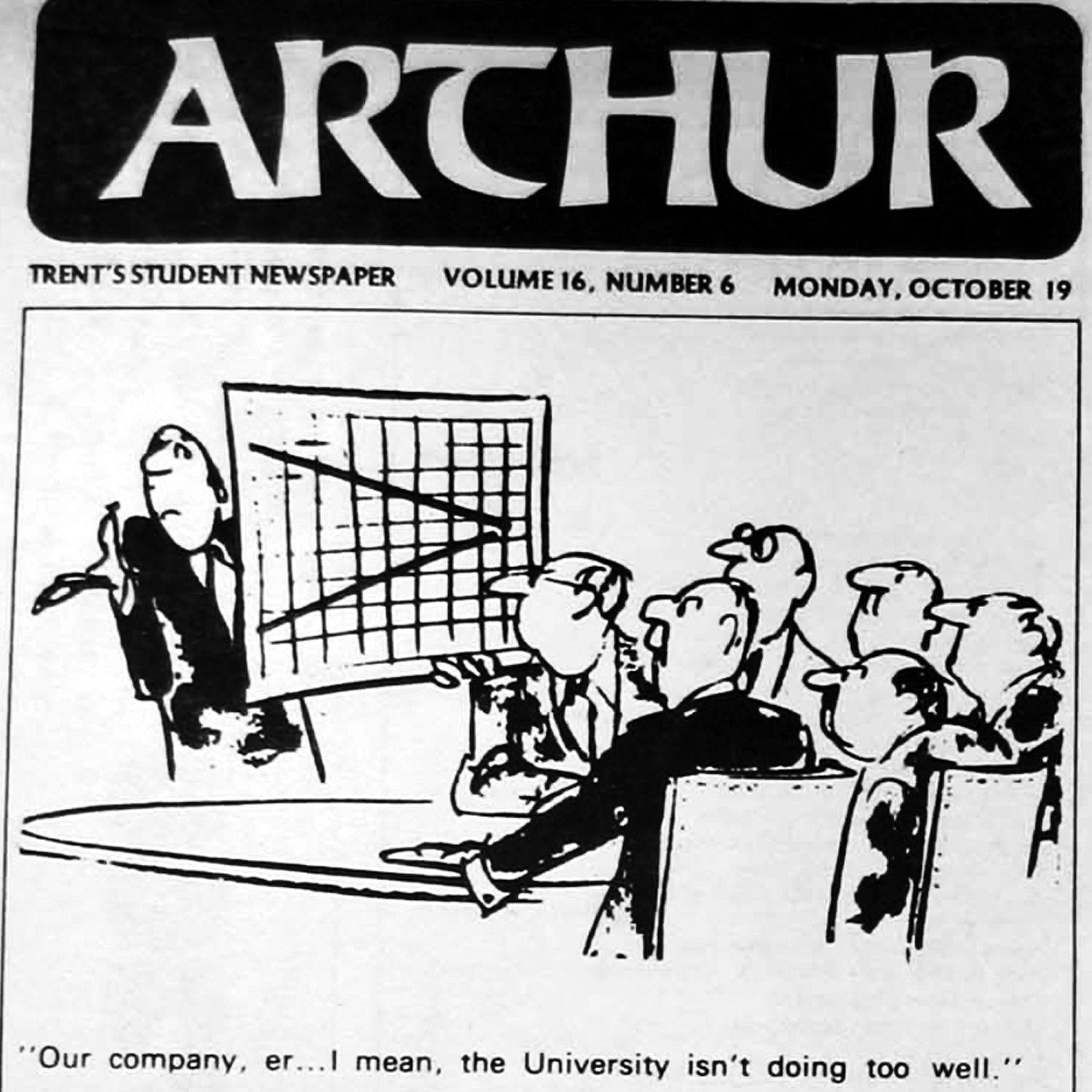

The Progressive Conservative government of Ontario, led by Premier William Grenville Davis, has just announced that tuition fees across the province will increase 12.2% by 1983. The headline of Arthur Newspaper reads: “Trent’s tuition likely to exceed $1000 next year.”

The government’s announcement comes with a warning: universities operating under a deficit may be dissolved and placed in the government’s financial control, effectively negating all contracts held between universities and their faculty and staff. The government does not mention that half of the universities in Ontario (including Trent University) are carrying deficits due to a 12% cut to their funding over the past five years. This means that university students are being asked to pay more for tuition while their institutions frantically make cuts to the services available to their students.

In light of the announcement, the Trent Student Union is organizing a day-long boycott of classes to protest underfunding of the university. It is set to take place March 11, 1982.

Fast forward 36 years and you’ll find that very little has changed. Except maybe the tuition fees.

In 2018, a different Trudeau is raising his children at 24 Sussex Drive. The Progressive Conservative Party runs the provincial government yet again. Tuition at Trent has gone from being just over $1000 to $6798.31. The provincial government is still making threats to its post-secondary institutions.

The Ford government made headlines in August when they announced that universities and colleges will face funding cuts if they fail to adopt a government-mandated free-speech policy that defends controversial speakers on campus.

In October, the Ford government announced that it will cancel over $300 million in funding for planned university and college campus expansions in Brampton, Milton, and Markham. The day after this announcement, Post-Secondary Education Minister Merrilee Fullerton made concerning ambiguous comments surrounding Ontario’s new free tuition program designed for lower-income households.

A few days later, an article was published in The Globe and Mail by Trent University President Leo Groarke, defending the Ford government’s position, while making questionable comments regarding the role of student fees in funding university growth.

The Trent Central Student Association has released statements denouncing both the government-mandated free speech policy and Groarke’s article in The Globe and Mail.

History repeats itself. And it’s no wonder — we are still grappling with the effects of neoliberalism several decades into its reign.

What is neoliberalism? This is a contentious topic. Many scholars locate its rise in the late 70s and early 80s, as leaders such as Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and Brian Mulroney came to power and implemented policies that would hurl Western society off the precipice of free-market capitalism. For our purposes, we will think of it as a set of policies that promote the privatization of public enterprise, the deregulation of business, and the implementation of austerity through tax cuts and the reduction of the welfare state. Essentially, we are witnessing the privatization and corporatization of the modern university. Students have effectively become nothing more than customers. And it’s terrifying.

In the following sections, I will try to explain how the very fabric of our university reflects this neoliberal ideology and how it all affects you — the student.

Tuition rates: how did we get here?

Now, of course it makes sense that modern day tuition would exceed that of 1982. It doesn’t take a brilliant economist to tell you that the cost of living has drastically increased over the last couple decades. However, inflation doesn’t actually provide much of an answer to the question at hand. In 1982, tuition cost approximately $1000 — after the 12.2% increase. However, with inflation, $1000 in 1982 would equate to $2517.82 in 2018. But tuition doesn’t cost $2517.82. It costs $6798.31 at Trent University — almost triple what it should be when compared against inflation.

1982’s announcement of a 12.2% increase in tuition was just the beginning of an attack against publicly funded, post-secondary education that would span decades, involving various levels of government.

One of the milestones in this trend is the 1995 federal budget drafted by former Finance Minister Paul Martin under the Chretien government. It marked the largest ever cut to social spending in Canadian history: the federal government made $25 billion in cuts. Much of the budget cuts came in the form of decreased funding for provinces, which meant less investment in healthcare and education. In Ontario, premier Mike Harris made a colossal 25% cut to post-secondary education, putting the onus on students to make up the difference. The Canadian Federation of Students reported that in 2014, “[student] fees accounted for almost 51 per cent of university operating budgets.” This is the epitome of neoliberal policy.

In 2017, Leo Groarke announced that Paul Martin — the man responsible for the budget that drastically increased tuition and student debt — was to receive an honourary degree from Trent University at convocation.

International student fees

If you found the figures for the rising domestic student tuition rates to be concerning, you should brace yourself for the fees international students incur during their time at Ontario universities. Amidst the 1982 announcement that tuition fees would increase 12.2%, international students were told that they wouldn’t be so lucky. The provincial government declared that international student fees would rise over 70% in the next year.

Again, 36 years later, not much has changed. At Trent, international student tuition is over triple that of domestic students. During the 2018 to 2019 academic year, international students will pay $20366.57 — a figure that has risen since last year. The numbers at Trent are indicative of a larger trend taking place across the province. In Ontario, the average cost of tuition for international students has risen from $25000 for the academic year in 2014 to $34000 for the year in 2018.

According to the Canadian Federation of Students, “Increases in tuition fees are the result of successive provincial governments divesting resources from public post-secondary education… [resulting in] institutions turning to differential fees as a strategy to generate revenue.”

In his opinion piece for The Globe and Mail, President Leo Groarke confirmed this practice, writing, “Educationally, students are our raison d’être. Financially, they provide the revenue that university and college budgets depend on. Institutions have tried to manage a difficult situation by dramatically increasing their numbers of international students.”

This coercive practice was made possible under the Mike Harris government in 1996 that effectively discontinued institutional funding for international students. The Canadian Federation of Students reports that “[i]nstitutions are free to raise international tuition fees as they see fit, in some cases, leading to fee increases of up to 50 per cent in a single year.”

It is worth noting that international students are not citizens and therefore cannot vote to elect legislators who will advocate for their right to affordable education.

Emphasis on STEM: a liberal arts school no more

Established in 1964, Trent emerged as a liberal arts school with great support from the community. 54 years later, it no longer has a reputation of being a predominantly liberal arts institution. Instead, great strides have been made in establishing Trent as a cutting-edge institution for STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) students to attend.

One need not look any further than the types of programs that receive more publicity and funding than others. Much publicity is focused on Trent’s School for the Environment. There has been a great effort to paint Trent as a world-leading school for environmental sustainability; however, this sentiment is not always reflected in its practices.

Much controversy has been raised surrounding the development of Trent University’s wetlands for the construction of a Twin Pad Arena and Swimming Pool Complex, a project that local environmental and Indigenous activists have denounced vehemently. It would appear that the university’s environmentalism has its limits and it seems as though the limit lies in widening profit margins — a most neoliberal characteristic.

Recent announcements surrounding investment in certain departments indicate a prioritization of science over the arts. On October 9, Peterborough MP Maryam Monsef announced a $2 million investment in ‘science and research’ at Trent University.

This trend is also evident in the annually updated Trent guidebooks. The university recently announced that it will add a Chemistry-Chemical Engineering Dual Degree Program in partnership with Swansea University. Trent has also announced “the addition of two new Bachelor of Science degrees and a specialization, making the breadth of forensic programming at Trent among the best in Canada.”

Where are the investments in the social sciences, humanities and the arts? Where are the new programs being rolled out in these sectors?

They are few and far between. Are these programs not part of the future of Trent?

One might think that they were not, if they were to look at the employment page of the University’s website. Under job postings for full-time faculty positions, there are tenure-track positions available in Nursing, Accounting, Mathematics and Chemistry. There is one full-time position available in the Child and Youth Studies Program offered at Trent University Durham. It is the only posting of its kind. It is important to take notice of where tenure-track positions are being allocated, and more importantly, where they are not.

Administrative Positions and Precarious Labour

One of the key markers of the neoliberal era has been ever-growing wealth inequality. The working class struggles to make ends meet while the bourgeoisie lines its pockets. This trend is made tangible in the salaries of corporate elites, as CEOs’ incomes climb and workers’ wages remain stagnant. While Trent University is not a corporation quite yet, its President — the equivalent of its CEO— earns over $300000 per year. This number seems quite staggering as Trent University looks for ‘efficiencies’ to be made through precarious labour practices.

In 2014, contract faculty at Trent were in a position to strike due to job insecurity and unequal wages in comparison to their full-time counterparts. At the time, Arthur reported “there [were] roughly 250 contract faculty at Trent, teaching approximately 25-30 percent of the courses offered here. These courses account for $28 million in incoming revenue for the university.” Neoliberalism has ushered in an unprecedented rise in precarious labour across the country and Trent University is no exception.

***

If the university is going to treat its students as customers, then it mustn’t abandon one of the major tenets of the neoclassical economic model that neoliberalism arises out of. Under this model, it is consumers who control the products that are available to them through the laws of supply and demand. Trent, and other universities who embody this trend towards neoliberalism must be careful not to alienate their customers. If students really are the ‘raison d’être d’etre’ Leo says we are, then why isn’t the University intent on keeping the customer happy?