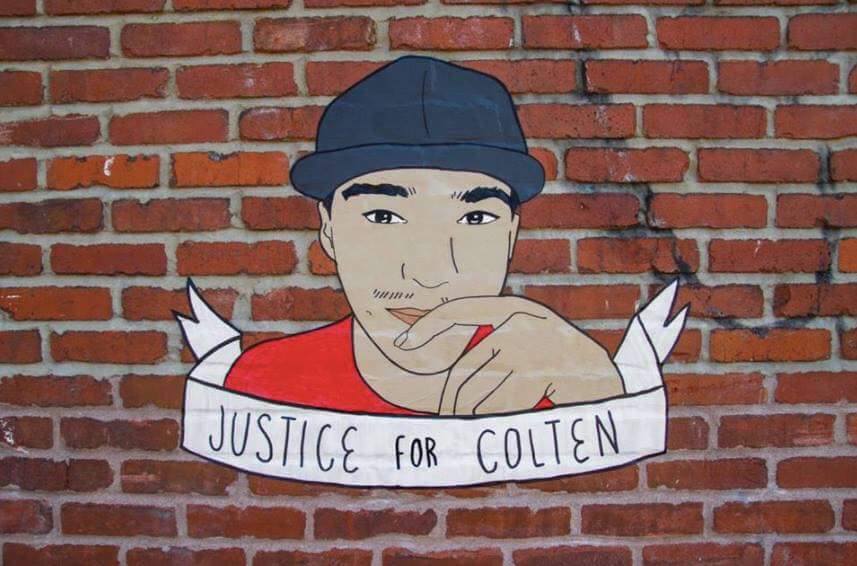

On August 9, 2016, a 22-year-old Indigenous man from Red Pheasant Cree Nation in Northern Saskatchewan was murdered. His name was Colten Boushie. He was a brother, cousin, son, nephew and friend.

His murderer is a 56-year-old white farmer named Gerald Stanley. On February 9th, the all-white jury tasked with declaring Stanley’s guilt or innocence chose to let a murderer walk free. Gerald Stanley was deemed ‘not guilty’ and acquitted of the charge.

A year and a half after Colten’s death, the Boushie family is left to grapple with the compounded trauma that this verdict brings forth.

This gross miscarriage of justice epitomizes a much broader, systemic issue throughout Canada as Indigenous peoples are forced to endure the repercussions of colonization. Boushie’s death has put contemporary settler-Indigenous relations in the national spotlight as Indigenous activists and allies mobilize to voice their solidarity with the Boushie family, as well as their indignation in the face of a broken and downright racist justice system.

One such expression of solidarity took place in Confederation Square on February 10 as over 50 members of the Nogojiwanong/Peterborough community came together to share in song and ceremony, honouring Colten Boushie’s life while discussing the need for a dismantling of this colonial system that has perpetuated systemic racism and done little to actualize justice for Indigenous peoples.

The vigil began with a smudging while Thohahente Weaver, an Indigenous community leader who played a key role in the event’s organization, gave his remarks. He spoke of the need for healing within the Indigenous community: “We lost a young man over a year ago; we lost several young people in Thunder Bay; we lost Tina Fontaine. We’ve lost many of our young people… I thought ‘we need to do something in Peterborough.’”

For many in the Nogojiwanong/Peterborough community, Boushie’s death and the results of the trial that ensued hit close to home. Crystal Scrimshaw — who, like the Boushie family, is Cree — touched on how the death of Colten Boushie resonates with her on a very personal level: “During the same time that Colten was murdered, I had a nephew that was murdered. His verdict came through two months ago, and that man got a life sentence for his murder, and when I heard the verdict of this man — not guilty and acquitted — it tore me up because I didn’t think a life sentence was enough for the man who took my nephew away, let alone someone who got acquitted. It is unspeakable.”

After the vigil’s organizers had spoken, people joined in drumming and singing while others offered tobacco to the fire burning at the centre of the vigil.

Although Colten’s murder happened in Northern Saskatchewan, it is important to recognize that it could have happened anywhere in Canada; racism against Indigenous peoples is a widespread problem that we all must play a role in addressing and ameliorating if justice is going to be actualized.

During the first weekend of February, two Indigenous people died in Timmins, Ontario in two separate interactions with law enforcement — one of which was shot and killed by police. This must be looked at in a broader scope of systemic racism as the Canadian justice system has been responsible for overwhelming inaction surrounding the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women, racial profiling of Indigenous peoples, and a clear overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in Canadian prisons.

At the end of the vigil, I spoke with members of the Trent University Native Association (TUNA), who spoke of the need for showing solidarity with Indigenous peoples.

Vice President of TUNA, Denise Miller, said, “We come from a community with a lot of trauma and a lot of strength that comes with that, but I think it is important to show that we are all struggling but no matter where we come from, we are always going to be together in the struggle of being Indigenous in Canada.”

Co-President of TUNA, Jaimee Lazore, continued, saying, “I think [showing solidarity] is important because… we are all struggling in this settler-state and the way we show solidarity through caring, raising awareness and standing strong.”

When asked about what non-Indigenous people striving to be allies can do to play their part in decolonization, Miller said, “Show up… When we’re talking about allyship, people only show up when there is a death, but it should be an everyday thing.”