It’s a commonplace, but an important one, that what the university is is always contested and complicated, and what any university is in any particular time and place is a snapshot of an instant in an ongoing struggle. Clark Kerr, who had the dubious honour of running Berkeley during the Free Speech Movement, once wrote that “the university is so many things to so many people that it must, of necessity, be partially at war with itself.” I’m going to argue that the university today has a hybrid role – a role that, owing to its various parts and their interaction, is at least somewhat impossible.

On the one hand, universities are instruments of upward mobility for students, as they have been for nearly a century. This work has been made more challenging in recent years by the ever-changing demands of the private job market which has little use for generally educated graduates, and wants post-secondary institutions to provide custom training for any future employees they may want to hire; and by the system of student loans that leaves students with an often overwhelming tax on any future happiness and freedom, all but nullifying the advantages of increased employability.

On the other hand, universities are also institutions for the preservation and renewal of cultural and scientific knowledge, a role it struggles with because there is so little agreement on what cultural knowledge is worth preserving and renewing, and because universities are replacing permanent faculty with contract instructors who are not paid to research. These roles tend to conflict with each other, particularly in a context of increasing inequality, but there is some hope for a change coming.

/ / /

In its origins, the university was a cloister, a rigidly conservative, exclusive institution that not only kept outsiders out but did it most vital intellectual work by negation: discrediting bad or dangerous ideas, rather than producing new and original ideas.

A university education was an ostentatiously useless accessory of gentlemanly leisure, providing privileged access to a fixed cultural repository – the canon – that students were taught by the faculty to protect, learn, and celebrate in connoisseurial contrast to the brutish cultural knowledge most people held.

The university also had a vital role in gate-keeping the learned professions: chiefly theology, but also law and medicine, policing the qualifications and behaviours of their members and members-to-be. It is this role that Immanuel Kant had in mind when he penned The Conflict of the Faculties, an early defense of academic freedom that argued that universities best serve power by pushing against the dominant stream of acceptable opinion – an idea that still resonates in current discussions of the role of the university.

Pure research was a relatively late development in most universities. Universities’ preserving role seemed to mitigate against a place for cutting edge research – especially in philology and natural history, where the truths of the Bible and the wisdom of the ancients were being rapidly torn to shreds – alongside the careful instruction in religious orthodoxies. The German universities, where the PhD was invented, served as models for first the Americans and then the world with their idea that pure science benefits the nation both in eliminating errors and in determining who is most qualified to teach young adults to think.

But universities nonetheless entered the last century with a defining tension between respectful conservatism and fearless innovation in the service of the nation.

/ / /

The university’s transformation into an instrument of upward mobility – what Jeffrey Williams calls the welfare state university – was related to changes in work, technology, and literacy, but fundamentally was an outcome of politics, specifically the politics of the world wars and the Great Depression. The value of established ideas plummeted when the stock exchanges crashed, and the impossibility of the freedom of a normal life for several decades produced a profound alienation from the political status quo.

When fascism was defeated in 1945, anti-fascism became kaleidoscopic, a multifarious egalitarian remaking of the world: decolonization, civil rights, public spending and taxation, public education, art and ideas, all reflected a belief in the nobility of all humanity. Universities expanded, admitted the working-class, women, and ethnic and racial minorities, and provided graduates with a membership card to an expanded middle class. Like housing initiatives and labour reforms that allowed a measure of stability to more workers than ever before, university education gave people a foundation for a better life, in which leisure was a common property.

Trent is a less obvious welfare state university than Carleton or York, and in some ways was swimming against the current. But the fact that it began as an idea at a meeting of Peterborough’s Labour Council speaks to the values of the post-war moment. Trent’s original ambitions reflected the immense confidence in the power of imagination in that era.

Austerity impinged almost immediately, and the buildings became less majestic and the tutorials less tiny as the years passed. The first faculty were institution-builders, largely indistinguishable from the administration; they unionized, and they fought every cost savings tooth and nail, so the process moved slowly, and created a byzantine set of obstacles.

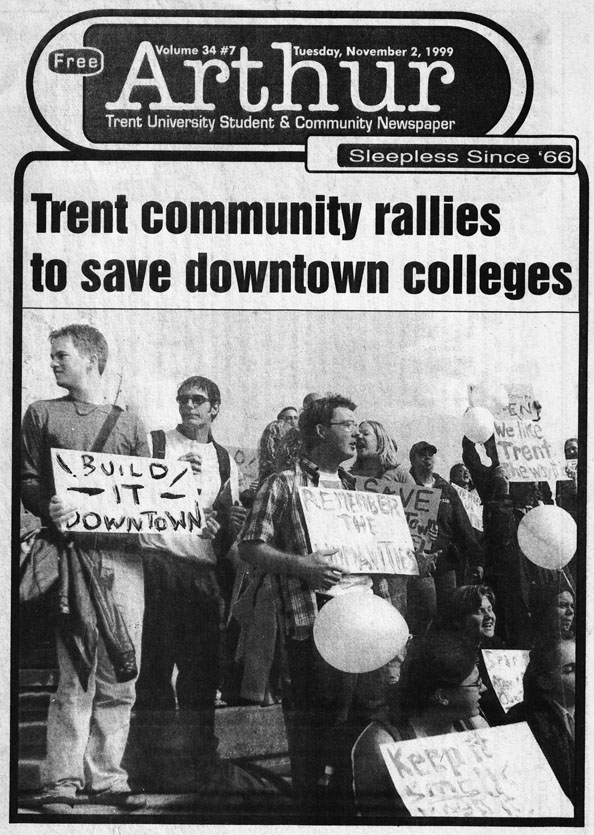

What is remembered as the fight over the fate of Peter Robinson College circa 2000 was really a fight over who controlled the university. A few buildings got shut down, and a few changed hands, but the real legacy of that era was norm erosion: Bonnie Patterson and her allies ran roughshod over the Trent way, eagerly transforming a weird and wilful university into a normal managerial dystopia. It took a long time to work itself through completely, and by then, conditions had changed.

/ / /

Because of the centralized nature of our banking sector and the comparative weakness of institutional endowments, Canada was somewhat insulated from the most devastating effects of financial crisis as seen in American colleges and universities. But not completely insulated: deficit politics in the 90s starved universities of funding and shifted the cost of education squarely onto graduates’ shoulders, while soaring housing costs and dismal job prospects dimmed hopes for upward mobility.

Tuition has gone up precisely at the same time as universities have failed to renew their faculties. Contract instructors making less than permanent professors teach increasingly expensive courses to students who juggle part-time jobs in order to ease their debt burden upon graduation. In new programs that purport to train graduates for very specific earning opportunities, the margin is even wider, and the exploitation of students and instructors alike more brazen.

Inequality among faculty is increased by showy research funding programs like the Canada Research Chairs that pluck promising young faculty out of the classroom and into a kind of permanent sabbatical. It’s easy to imagine a future university in which there is no tenure-track faculty, only ruthlessly exploited contract employees teaching courses and a handful of star researchers bringing in grant money.

It’s harder to picture, but possible, another scenario: that unions of students, staff, and various types of instructors will push the administration to make the university a better employer, an embodiment in its day-to-day functions of the social justice curriculum the university is already famous for. Above and beyond collective bargaining and coordinated campaigns of solidarity between unions that would be the necessary instrument of such a transformation, such a future – a university-to-come – would depend on a leap of imagination among the university’s students, teachers, and staff as to what the university is and could be.