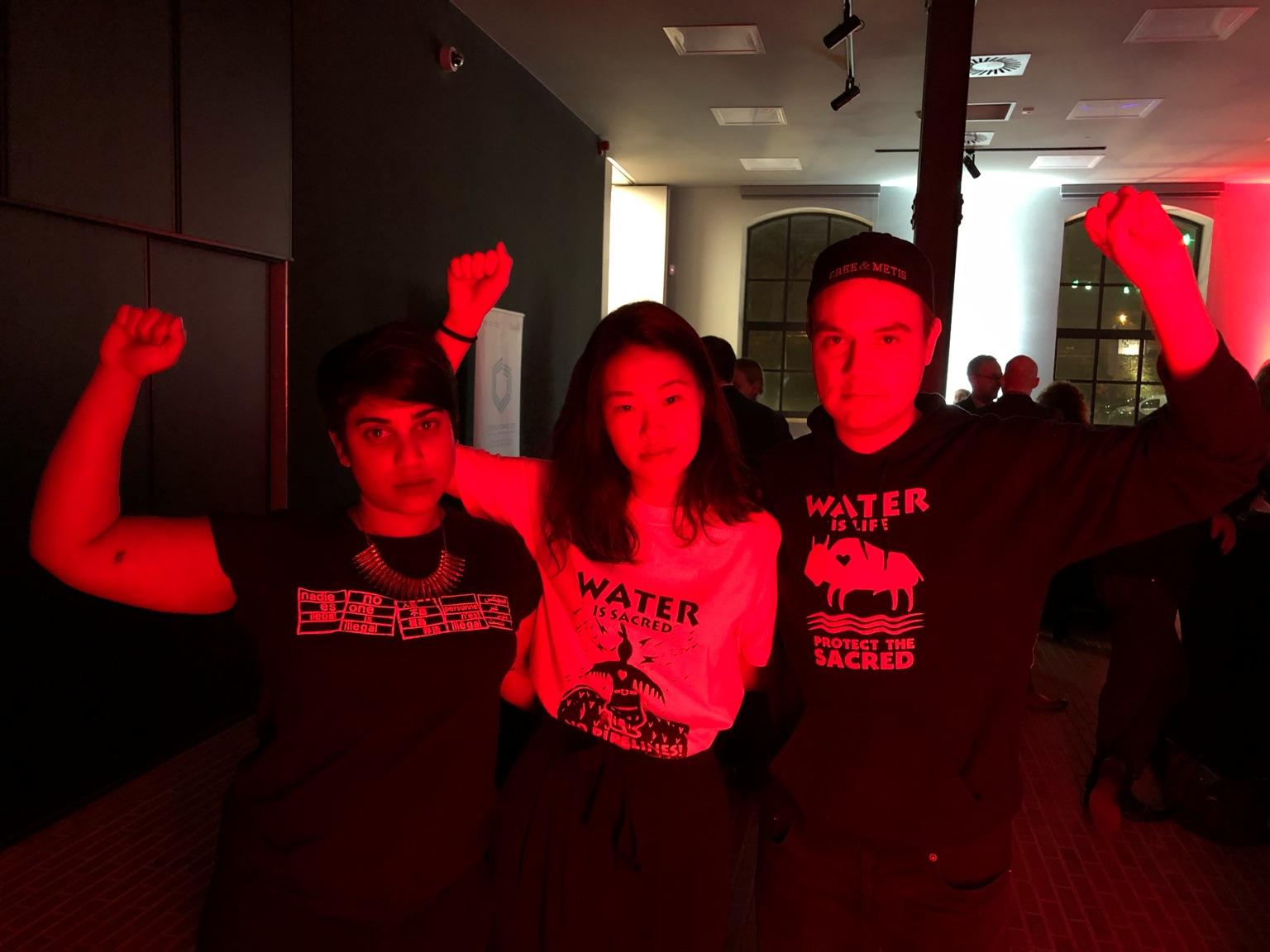

A year ago, the Trent community was challenged in its understanding of whiteness and anti-racism when the TCSA hosted an event called “It’s Okay to Be (Against) White(ness).” White nationalists came out of the woodwork and we made the news. I am sure I am not alone in feeling that there is a lot of learning that our community needs to do.

For the past four years, I have been engaged in these conversations as a student at Trent University, as a student organizer through the TCSA, and as a community organizer in Peterborough. Long story short, talking about racism and anti-racist work is tiring, especially when talking about these things with white settlers.

This article is a response to all white settlers who don’t like talking about their privilege and become upset when called to do better. It is also for those Black, Indigenous, and racialized community members who share my exhaustion in navigating white settler tears in doing anti-racist education. The generosity of it will not be grasped by some white settlers, I am sure, but that does not mean it will not be helpful. I hope that it can be a continuation of the very generous, kind, and patient work I know so many of my fellow Indigenous community members do every single day.

I use “anti-oppressive” and “anti-racist” interchangeably throughout this article, but not because they are the same. Anti-racism is one of many anti-oppressive strategies. But these tools for white settlers engaging in anti-racist learning are transferable to other positions of privilege and forms of anti-oppressive learning. They can be helpful to men unlearning toxic masculinity. To straight folks unlearning heteronormativity (the misconception that straight is normal, and everything else is not). To cis-gender folks (folks who are not trans or non-binary) in unlearning biological essentialism (the misconception that genitalia = gender and that trans people do not exist) or cis-normativity (the misconception that cis-men and cis-women are normal, whereas trans folks and non-binary peeps are not).

So here are 5 Anti-Oppressive Tools:

1. Do not run away from whiteness and the privilege it gives you. I say this as a white-passing Indigenous student – as a Queer Cree, Métis, and “Something-European” Reginan1 who literally looks like he got off a boat from Europe. This is one thing that many white settlers get stuck with in doing this learning. Part of this is because whiteness, as a construct, has not always included everyone. At one point, it excluded the Irish and Italians. Moreover, Europe was and is a complicated place and many white settlers have family legacies of fleeing violence and seeking refuge. And just because white settler privilege exists today, does not mean that white settlers cannot be impacted by other systems of oppression. Homophobia and Transphobia still impact white Queer and Trans folks. Misogyny and gendered violence still impact white women and white Trans folks. But as my browner and Black kin remind me, as the white-passing Queer Cree, Métis, and “Something-European” Reginan I am, I will never be targeted by institutional violence because of my skin colour or other physical features. Visibly-racialized folks (folks who do not look white and will never be assumed to be white) face all these things that we (white settlers, white-passing Indigenous folks, and white-passing people of colour) face, but then experience another level of oppression in their lives, especially in this very-racist settler-colonial state in which we all live (Canada). We can’t run from white-passing and white settler privilege if we want to do anti-racist work. We must acknowledge it and position it to be useful to our visibly-racialized community members.

2. Everyone has feelings and feelings are part of processing, but while that may be the case, not everyone is equally responsible for holding space for all feelings. White settlers may become defensive, uncomfortable, or emotional, especially those who are new to anti-racist learning. These feelings are okay. What isn’t okay is white settlers expecting emotional support from or blaming Indigenous People and People of Colour for their feelings of discomfort when doing anti-racist learning. We all have feelings and we need to own them, especially while we process and accept our privilege. What I have come to learn is that white settlers don’t often know how to separate their mental health from their learning about and reflecting on their white settler privilege. Or to be more clear: white settlers do not take responsibility for their self-image as white settlers (which is how white guilt forms) especially in relationships with very generous Indigenous Peoples and People of Colour in their lives.

3. Talking to white settlers about race or colonialism is not about getting them to hate themselves. I don’t know a single Indigenous Person or Person of Colour who is out there doing anti-racist education to white settlers with this intent. Racism and colonialism operate to convince Indigenous Peoples and People of Colour that we are “less than” white settlers: that we are ugly, stupid, unprofessional, disorganized, backward, superstitious, violent, dangerous, etc. As Indigenous Peoples, we even had this self-hatred institutionalized in the form of residential schools — our Elders frequently tell us how they were taught to hate themselves by their teachers. Why would we want to replicate this on white settlers?

4. Forming Relationships through Anti-Oppressive Learning isn’t the goal, but it is a gift. Although accountability and the development of good relationships go hand-in-hand with anti-oppressive work, not all relationships work out. Sometimes in our anti-oppressive learning we cause, uphold, or acquiesce to harm that is rooted in oppression that impacts other people, and these individuals make the choice to end relationships with us. This can be difficult, for sure, but boundaries are boundaries and once established need to be respected. No amount of time we share with anyone will mean that we are entitled to a relationship with them after they decide otherwise. Moreover, we can also advance our anti-oppressive learning, recognize the harm we caused, upheld, ignored, and/or failed to notice, and apologize for that harm, but find that they do not wish to reconcile and that those boundaries remain intact. We may feel guilty when this happens. We may feel like we are terrible and unforgivable. We may loathe ourselves. But it is our responsibility to recognize our negative self-image, process it, forgive ourselves, and remember the importance that anti-oppressive learning can have for building positive relationships in the future. As an Indigenous student in this community who has established boundaries with many white settlers after they have caused, upheld, or acquiesced to harm derived from white settler privilege or white guilt, my only hope is that they learn from that harm. Everything in life teaches us. Even the difficult things. They don’t need me in their lives to continue their anti-racist learning, but that doesn’t make it any less important to do.

5. Remembering to re-center migrant, visibly-racialized, and femme WoC2 and QTBIPoC3. Sadly (and with great difficulty), I have come to accept that white settlers in my life will never be able to reciprocate my level of care in anti-racist work. A white settler will have done the harm that they have done to me and my community, and may never be accountable to that harm. My response is to try to make something good and helpful from that pain. As shared above, everything in life teaches us. This attack can be a lesson to white settlers to be kinder to themselves and to each other. For me, it has been a lesson that this recognition of non-reciprocated support is how migrant, visibly-racialized, and femme WoC and QTBIPoC probably feel from the entire world while resisting femmephobia, Transphobia, and gender-based violence within our communities, resisting racism, colonialism, Transphobia, xenophobia, and gender-based violence from the State, and raising our families. As reflected above, I must consider my own privilege in my anti-oppressive work. Although the jury is still out on my gender identity, I am perceived to be a man and am treated as though I am a man. Although I am Cree and Métis (“Indigenous”), I have white-passing privilege. And although Canada, as a settler-colonial nation state, erases my nêhiyaw and Métis languages and teachings to replace them with English and British-derived common law, and continues to uphold structural and genocidal violence against my nêhiyaw and Métis relations, Canadian citizenship and proficiency in English allow me some measure of security that undocumented folks and migrants do not have. I need to humbly acknowledge that I have not and probably will not come close to reciprocating the support that migrant, visibly-racialized, and femme WoC and QTBIPoC have so generously given me in my life. I hope white settlers take care of themselves, but then I hope we can all sit with this specific lesson.

Êkosi. That’s it.

Read more of Brendan’s writing by clicking here.